DETERMINING DAMAGE TO COMPUTER NUMERICALLY CONTROLLED

(CNC) MACHINES

By

Charles C. Roberts, Jr., Ph.D., P.E.

Computer numerically

controlled (CNC) machinery is at the heart of automated manufacturing

throughout the world. CNC machines,

selling for prices in excess of a half million dollars, are manufactured by

many companies, often overseas. A typical example is shown in Figure 1. The

machines are manufactured and tested at the manufacturer’s plant with records

kept as to their precision and accuracy. The machine is then packaged and

shipped to a dealer or customer.

Figure 1

The customer then has the

machine installed and made ready for production. In some instances, after a

small production run, the new owner’s quality control department discovers

severe tolerance problems with the product, suggesting that the machine is

damaged. There is no evidence of an impact on the machine, no scraped paint or

distorted components. The machine owner then makes a claim seeking coverage

under the transit portion of his policy. So how do you prove that the machine

is damaged, and that it is damaged as a result of transit or some other cause?

Analyzing CNC equipment can be a daunting task because of the complexity of the

equipment. However, a few basic concepts will go a long way to help prove or

disprove the existence of damage.

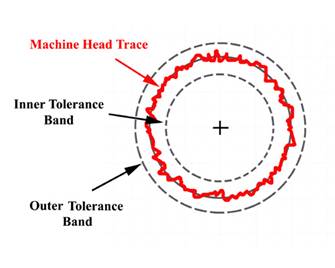

During production of the CNC

machine, testing was probably performed on the precision and accuracy of the

particular machine. The test diagnostic equipment, often a highly precise indicator

attached to the machine, will generate a test pattern similar to that shown in

Figure 2. The machine is programmed to draw

a circle and the precision indicator traces the path of the machine head (machine

head trace). The inner and outer tolerance lines show the limits for an

acceptable test, which often is less than 0.0001 inches. In Figure 2, the

machine accuracy and precision are acceptable. Precision is the ability of the

machine to repeat a particular point location of the head. The accuracy of the

machine is its ability to correctly reflect the location of the machine head. If

a test is performed at the insured’s location and a test pattern like that shown

in Figure 2 results, then it is unlikely that there was any damage to the

machine during transit or any defect in the machine during manufacture.

Figure 2

Figure 3

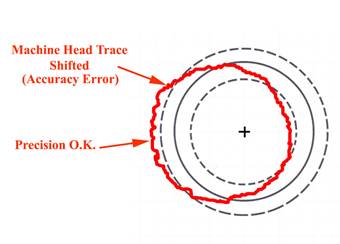

Figure 3 shows a test pattern

where the machine head trace has been displaced, such that it is out of

tolerance to one side. This is a typical accuracy error. The machine head is

not moving to the exact location of where it is programmed to go, but it is

performing this test repeatedly, so the precision is acceptable. This type of

error can occur from a sudden impact or drop of the machine during transit. Check

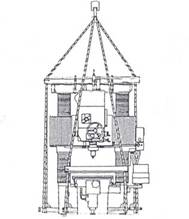

out the transit history. Was the machine properly lifted? Figure 4 shows

hoisting instructions for a particular machine using cables to prevent tipping.

If forklifts were used, this may violate shipping instructions. Some machines

are very top heavy and prone to falling over when using fork trucks. Dropping a

machine onto its base may show little physical damage but result in a test

pattern like Figure 3, suggesting severe internal damage.

Figure 4

Figure 5

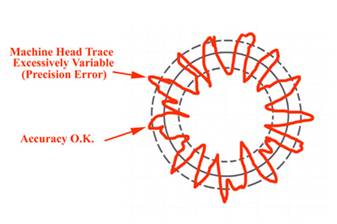

Figure 5 shows a variable

head trace pattern, which is a result of precision error. The machine cannot

repeat a particular head location, although the location is in the “ball park”

of where it should be. This type of pattern is usually not related to shipping

damage but more likely some problem with manufacture or remanufacturing of the

machine.

Working with the CNC machine

manufacturer can aid in obtaining documentation as to the initial condition of

the machine. On the flip side, the manufacturer may end up being a party to a

legal action and may not readily produce information. Working with the

transportation company has similar up and down sides and may yield information

as to the particular handling dynamics of the machine. Finally, a visit with

the insured’s production facility may yield more clues as to the cause of the

problem, which may have nothing to do with the transportation or manufacture of

the CNC machine.

Published in Subrogator

Magazine