Figure 1

Case studies are useful in explaining the various causes of fire related

losses in combine harvesters. Figure 2 is a front view of a combine

showing evidence of a fire origin in the engine compartment. The

vehicle was combining corn when the fire started. It should be noted

that the fire occurred in October, but the subrogation unit did not call

for an inspection until January. To blunt the spoliation argument,

inspection of the vehicle soon after the loss is desirable.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 3 is a close-up photo of the bell housing on the back of the

engine showing a faulted wire (white arrow) that had shorted to

ground at the bell housing. Inspection of the wire in an exemplar

combine showed the wire to be unsupported and resting on the bell

housing. The wire was subject to chafing (Reference 1) over time,

which damaged electrical insulation, resulting in the short circuit

related fire. Good engineering design of wiring harnesses includes

proper support of the wires to prevent wear from chafing. This was

absent in this case, suggesting a high probability of recovery from the

manufacturer. Not all wiring insulation breakdown in combines is a

result of chafing. Figure 4 shows insulation damage from rodents

(Reference 2). It is known in the industry that rodents chew on

polymer insulation, causing insulation breakdown and a possible fire.

Proper storage of the combine may be a factor with respect to rodent

infestation. Other types of biologic intervention such as bird nests

(Reference 3) on hot engine components can cause fires and be a

result of poor system design, such as lack of proper guarding.

Figure 3

A common cause of combine fires is straw or chaff build-up during

harvesting. Straw and other combustible dust tends to accumulate in

the machinery and can be ignited by a variety of ignition sources,

especially in exceptionally dry weather. Figure 5 shows such a build-up,

which is often addressed in operator’s manuals. Typical requirements

by manufacturers are to clean out the residual chaff once a day.

Subrogation potential is low for those cases where the operator

failed to follow the cleaning recommendations in the manual.

Figure 5

Figure 6

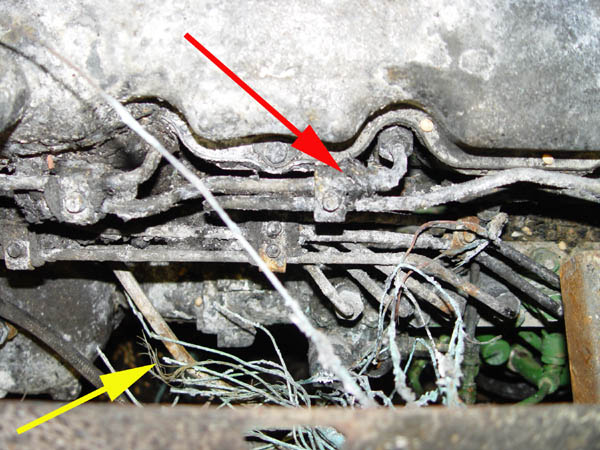

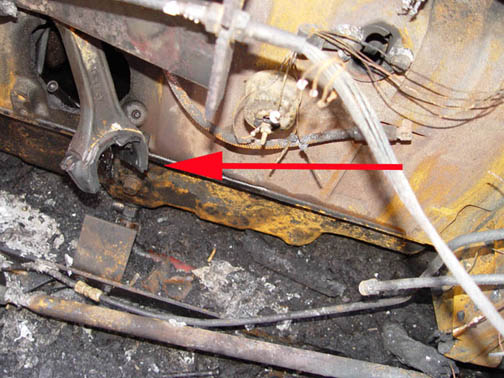

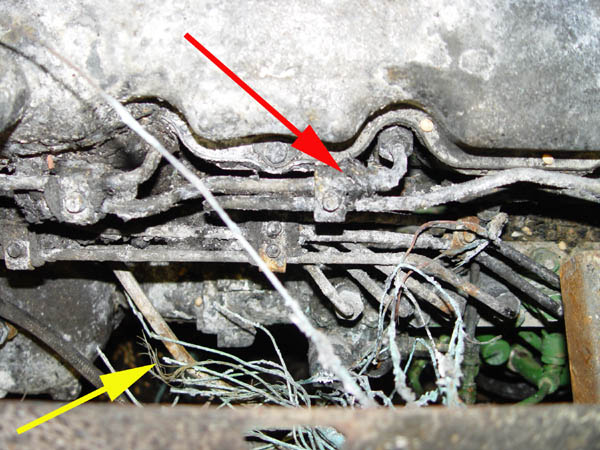

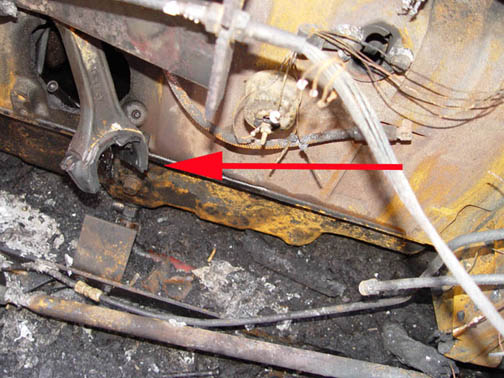

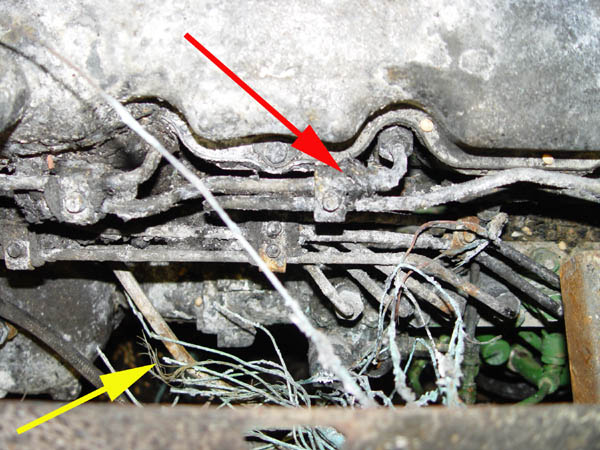

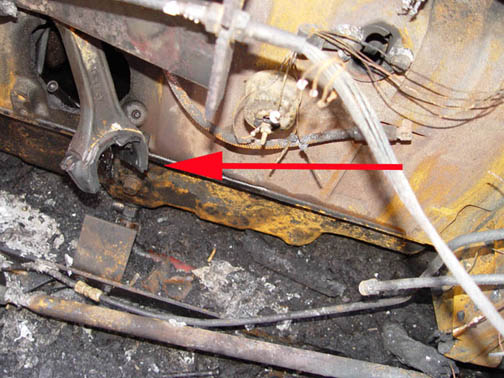

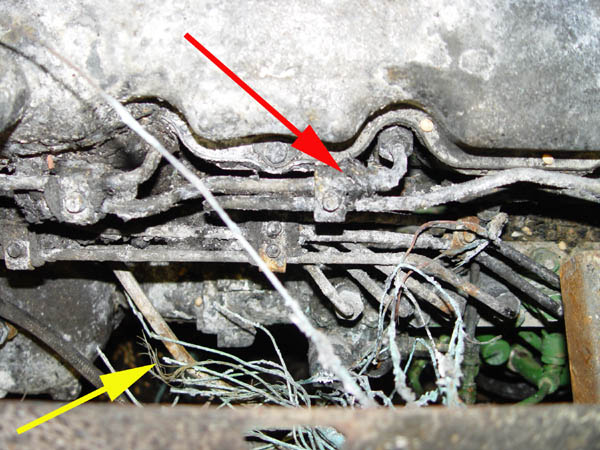

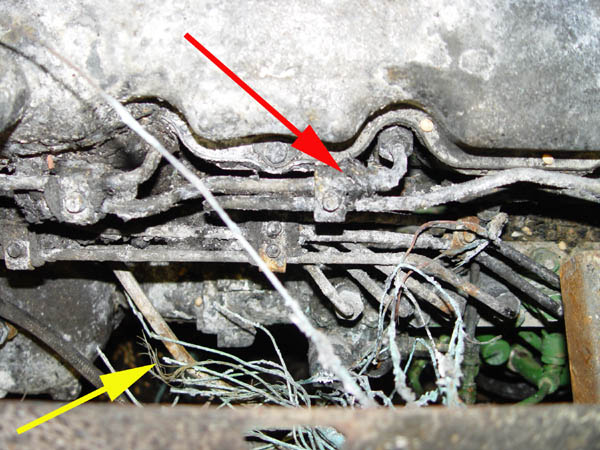

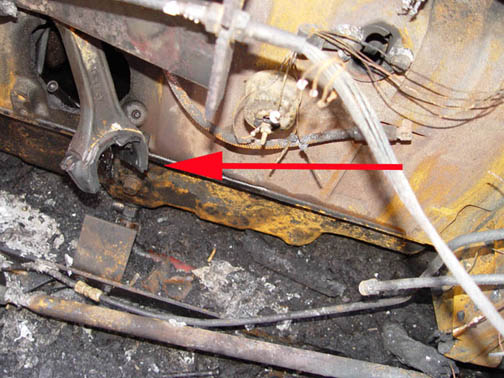

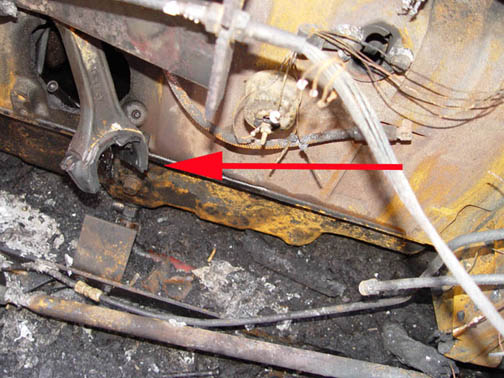

In Figure 6, the red arrow points to a fuel leak near a fuel line support

clamp. The fuel line leaked fuel as a result of a fatigue crack in the

fuel line. Ordinarily, the subrogation unit from the insurance

company would be talking to the manufacturers on this claim.

However, the insured owner of the vehicle noticed the leak prior to

the fire and failed to correct the problem, possibly reducing the

degree of recovery from the vehicle manufacturer. The yellow arrow

points to several faulted wires that are a result of the fire and not a

cause.

Figure 7

Figure 7 is a view of the side of an engine block on a combine, which is

at the origin of the fire. A connecting rod had failed and punched

through the block as indicated by the red arrow. This expelled hot oil

vapor, which was ignited by a variety of possible ignition sources in

that area. Many insurers would deny a claim of damage to the engine

as a result of a “mechanical failure” but would extend coverage to

that part of the machine damaged by fire. Mechanical failure can be

a result of wear out, improper design, improper manufacturing,

improper remanufacturing, improper repair and lack of maintenance.

In this case, engine wear out on an old vehicle was to blame,

suggesting a decreased chance for recovery.

REFERENCES

1. “Wire Chafing, a Cause of Electrical Fires,” Claims Magazine, April 1999.

2. “Rodent Damage to Automobiles,” Claims Magazine, December 1996.

3. “Biologic Intervention Can Cause Fire,” Claims Magazine, September 2002.

BACK TO C. ROBERTS CONSULTING ENGINEERS HOME PAGE,

WWW.CROBERTS.COM

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 3

A common cause of combine fires is straw or chaff build-up during

harvesting. Straw and other combustible dust tends to accumulate in

the machinery and can be ignited by a variety of ignition sources,

especially in exceptionally dry weather. Figure 5 shows such a build-up,

which is often addressed in operator’s manuals. Typical requirements

by manufacturers are to clean out the residual chaff once a day.

Subrogation potential is low for those cases where the operator

failed to follow the cleaning recommendations in the manual.

Figure 5

Figure 6

In Figure 6, the red arrow points to a fuel leak near a fuel line support

clamp. The fuel line leaked fuel as a result of a fatigue crack in the

fuel line. Ordinarily, the subrogation unit from the insurance

company would be talking to the manufacturers on this claim.

However, the insured owner of the vehicle noticed the leak prior to

the fire and failed to correct the problem, possibly reducing the

degree of recovery from the vehicle manufacturer. The yellow arrow

points to several faulted wires that are a result of the fire and not a

cause.

Figure 7

Figure 7 is a view of the side of an engine block on a combine, which is

at the origin of the fire. A connecting rod had failed and punched

through the block as indicated by the red arrow. This expelled hot oil

vapor, which was ignited by a variety of possible ignition sources in

that area. Many insurers would deny a claim of damage to the engine

as a result of a “mechanical failure” but would extend coverage to

that part of the machine damaged by fire. Mechanical failure can be

a result of wear out, improper design, improper manufacturing,

improper remanufacturing, improper repair and lack of maintenance.

In this case, engine wear out on an old vehicle was to blame,

suggesting a decreased chance for recovery.

REFERENCES

1. “Wire Chafing, a Cause of Electrical Fires,” Claims Magazine, April 1999.

2. “Rodent Damage to Automobiles,” Claims Magazine, December 1996.

3. “Biologic Intervention Can Cause Fire,” Claims Magazine, September 2002.

BACK TO C. ROBERTS CONSULTING ENGINEERS HOME PAGE,

WWW.CROBERTS.COM

Figure 3

Figure 5

Figure 6

In Figure 6, the red arrow points to a fuel leak near a fuel line support

clamp. The fuel line leaked fuel as a result of a fatigue crack in the

fuel line. Ordinarily, the subrogation unit from the insurance

company would be talking to the manufacturers on this claim.

However, the insured owner of the vehicle noticed the leak prior to

the fire and failed to correct the problem, possibly reducing the

degree of recovery from the vehicle manufacturer. The yellow arrow

points to several faulted wires that are a result of the fire and not a

cause.

Figure 7

Figure 7 is a view of the side of an engine block on a combine, which is

at the origin of the fire. A connecting rod had failed and punched

through the block as indicated by the red arrow. This expelled hot oil

vapor, which was ignited by a variety of possible ignition sources in

that area. Many insurers would deny a claim of damage to the engine

as a result of a “mechanical failure” but would extend coverage to

that part of the machine damaged by fire. Mechanical failure can be

a result of wear out, improper design, improper manufacturing,

improper remanufacturing, improper repair and lack of maintenance.

In this case, engine wear out on an old vehicle was to blame,

suggesting a decreased chance for recovery.

REFERENCES

1. “Wire Chafing, a Cause of Electrical Fires,” Claims Magazine, April 1999.

2. “Rodent Damage to Automobiles,” Claims Magazine, December 1996.

3. “Biologic Intervention Can Cause Fire,” Claims Magazine, September 2002.

BACK TO C. ROBERTS CONSULTING ENGINEERS HOME PAGE,

WWW.CROBERTS.COM

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 7 is a view of the side of an engine block on a combine, which is

at the origin of the fire. A connecting rod had failed and punched

through the block as indicated by the red arrow. This expelled hot oil

vapor, which was ignited by a variety of possible ignition sources in

that area. Many insurers would deny a claim of damage to the engine

as a result of a “mechanical failure” but would extend coverage to

that part of the machine damaged by fire. Mechanical failure can be

a result of wear out, improper design, improper manufacturing,

improper remanufacturing, improper repair and lack of maintenance.

In this case, engine wear out on an old vehicle was to blame,

suggesting a decreased chance for recovery.

REFERENCES

1. “Wire Chafing, a Cause of Electrical Fires,” Claims Magazine, April 1999.

2. “Rodent Damage to Automobiles,” Claims Magazine, December 1996.

3. “Biologic Intervention Can Cause Fire,” Claims Magazine, September 2002.

BACK TO C. ROBERTS CONSULTING ENGINEERS HOME PAGE,

WWW.CROBERTS.COM

Figure 7

REFERENCES

1. “Wire Chafing, a Cause of Electrical Fires,” Claims Magazine, April 1999.

2. “Rodent Damage to Automobiles,” Claims Magazine, December 1996.

3. “Biologic Intervention Can Cause Fire,” Claims Magazine, September 2002.

BACK TO C. ROBERTS CONSULTING ENGINEERS HOME PAGE,

WWW.CROBERTS.COM

WWW.CROBERTS.COM