EVOLUTION OF AUTOMOBILE ACCIDENT

RECONSTRUCTION

(Published in Subrogator

Magazine, Fall 2007)

By

Charles C. Roberts, Jr., Ph.D., P.E.

In the “old days,” automobile

accident reconstruction testimony was often offered with little scientific or

computational basis. Controlled (expert) witnesses would offer estimates of

impact speed based on, for example, years of experience as a police officer

attending to actual automobile accidents.

With the advent of more scientific approaches where calculations are rooted

in laws of physics, accident reconstruction has evolved into a more scientific

methodology utilizing computers for calculations (Ref 1) and instruments for

testing automotive vehicles. Still, some jurisdictions gave more weight to

eyewitness testimony speed estimates of a vehicle than to speeds determined by

scientific means (Ref 2). An eyewitness

may be able to testify that a vehicle was traveling in a certain direction, but

is unlikely to offer accurate testimony as to the speed of the vehicle. Over time, the courts have come to realize

that scientific means have evolved in accuracy and can help the trier of fact.

Consequently, accident reconstruction analysis, which is scientifically based,

is now typically allowed in court, despite the existence of eyewitness

testimony. This article reviews what has changed and what remains

the same in accident reconstruction over the years.

Accident Scene Investigation

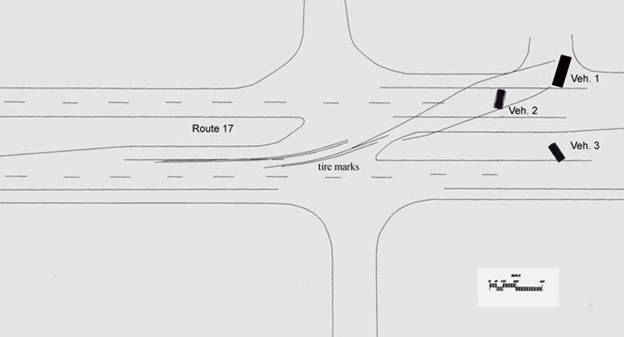

Classically,

accident scenes have been documented by film cameras and tape measurements. The

accident reconstructionist walks the scene, takes

measurements and documents on paper. With the evolution of inexpensive digital

technology, digital cameras have displaced the film camera, and electronic theodolite

(transit) measuring is beginning to displace manual measurements. For example, Figure 1 is a diagram of an

accident scene measured by an electronic transit, generated from total station

software. Total station is a measuring device used by land surveyors, but is

now being used by police departments and investigators to document accident

scenes. The instrument uses a light beam to measure objects at the scene and

converts this information to x, y and z coordinates. The data is then

downloaded to a CAD program for scene drawings and calculation purposes. There

are over 100 data points measured with the total station to generate the scene

diagram of Figure 1.

Figure 1

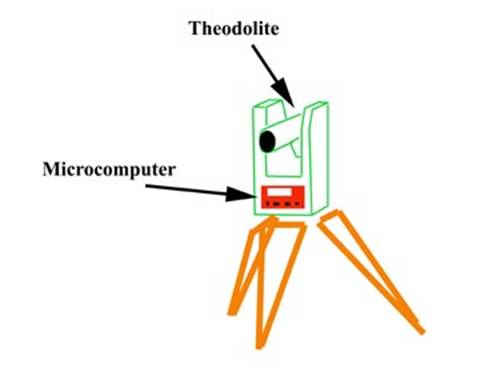

Figure 2

Figure 2 shows a drawing of a

typical theodolite with microcomputer measuring device and optical viewing

scope. The operator typically has a hand held device to download data from the

theodolite, to be used in the analysis. The advantage of the new technology is

more accuracy, more data points and less measurement time.

Figure 3

Another aid in analyzing the

accident scene is the availability of relatively high resolution satellite

imaging, as shown by the satellite photo of Figure 3. Resolutions on the order

of one foot can be purchased for many areas in the

Vehicle Inspection and Analysis

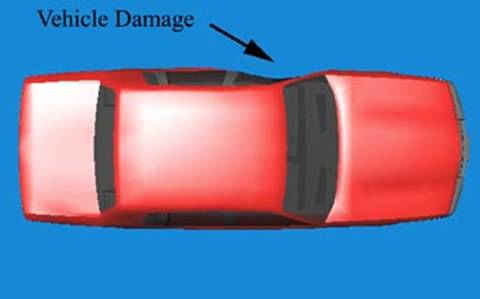

Vehicle damage pattern

analysis has always been an important aspect of accident construction and will

continue to be utilized in the future. The damage patterns help determine orientation of vehicles at impact and severity of

the impact. Some new technology that is

helping the reconstructionist, is the onboard data recording

technology available now in many new vehicles.

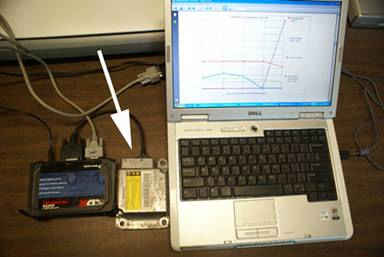

This includes the sensing diagnostic module for air bag deployment

(black box) as well as onboard trouble records in vehicle memory. Figure 4

shows a typical black box (they are actually silver), indicated by the arrow, being

downloaded to a lap top computer.

Figure 4

In this instance, the black

box was removed and connected directly to the computer because of severe damage

to the main vehicle electronic bus system. Many times, the data can be extracted

without removing the black box. Data

extracted from the black box includes vehicle speed, seat belt usage and

velocity change: a measure of the severity of the accident. See Reference 3 for

an article detailing black box technology. With the advent of anti-lock brakes

on vehicles, tire skid marks are less apparent, since the antilock brake system

is designed to reduce skidding. It is becoming more difficult for analysts to

measure these faint tire marks especially several days after the accident. The

black box speed data has evolved at the right time to offset this loss of data.

Other onboard data is

available through more advanced diagnostic tools (Figure 5) that store fault

codes on various processors throughout the vehicle. The tool is connected to

the DBR2 port on the vehicle and downloads information stored onboard the

vehicle. This information can give insight into the mechanical and electrical

condition of the vehicle and possibly signal the existence of a defective

condition in the vehicle that could have caused an accident.

Figure 5

Figure 6 is an example of

another electronic testing device, a brake performance analyzer. Mounted on the

dash, the vehicle is tested to determine if braking performance of a vehicle is

adequate. Data read-out is in G’s of

deceleration, or drag factor.

Figure 6

The Reconstruction

Hand calculations using

equations derived from scientific physical laws are still used in

reconstruction. However the proliferation of inexpensive computer technology

has spawned a variety of computer programs used

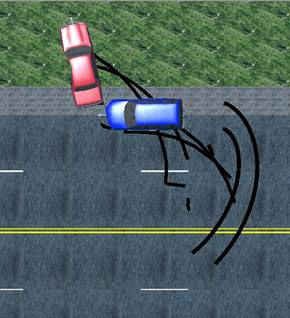

Figure 7a

Figure 7b

Figure 7c

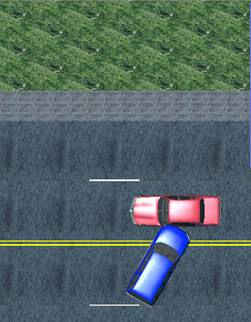

to calculate impact speeds and provide simulations of

the accident. Figure 7a shows impact

positions of two vehicles involved in an accident. Figure 7b shows the rest positions of the

vehicles, determined by scene data. The hypothesized impact and speed

conditions are input into the computer, and the results reviewed (Figure 7b).

If the rest positions from the calculation match the positions documented at

the scene, then the input data is most likely the impact speed and orientation

of the vehicles. Figure 7c shows vehicle

crush or damage calculated by the program. This is compared to the actual

damage to the vehicle as a measure of the accuracy of the calculations. The

program shown above uses the SMAC (Simulation Model of Automotive Collision) computer

analysis developed by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

Simulations can then generate animations. These are short videos of how the

accident occurred, which are good demonstrative evidence for a jury. The

computer programs utilize the same basic laws of physics as do the hand

calculations but are more rapid and many times more accurate. It should be

noted that the computer is not offering an opinion as to speed or impact orientation.

It is the reconstructionist

who offers the opinion based on scientific data and analysis tools (computer)

commonly used in the scientific community.

Accident reconstruction has

evolved and is adapting to new technologies. The once prolific skid mark has

been slowly disappearing because of anti-lock brakes, which leave little or no

tire mark. Black box data showing

pre-impact speed has replaced some of this information as software becomes

available to access this information. Despite all these new and improved tools

that are available,

the reconstrutionist is still the

ultimate formulator of opinions offered in court as to how an accident

occurred. Other articles that concern

accident reconstruction and may be of interest are outlined in References 4-8.

References:

1.

"Computerized

Accident Reconstruction," Insurance Adjuster Magazine, June 1983, p50f.

2.

Colonial Trust and

Savings Bank v. Kasmar, et al. Third District No-3-89-0034,

3.

“Black Box Aids

in Subrogation,” Subrogator, Spring/Summer 2004,

p104f.

4.

"Automotive

Lamp Examination," Insurance Adjuster Magazine, February 1984, p42f.

5.

"Response

Time," Claims Magazine, June 1998, p30f.

6.

"The

Anti-Lock Effect," Claims Magazine, March 1994, p69f.

7.

"Damage

Patterns on Vehicles Reveal Much for Accident Reconstruction," Claims

Magazine, June 1996, p36f.

8.

"Truck

Accidents - Investigating Probable Cause," Insurance Adjuster Magazine,

October 1985, p43f.